- Arts

- Academics

-

Athletics

- Athletics Overview

-

Upper School Teams

- Baseball - Varsity

- Baseball - Junior Varsity

- Basketball - Boys Varsity

- Basketball - Boys Junior Varsity

- Basketball - Boys Freshman

- Basketball - Girls Varsity

- Basketball - Girls Junior Varsity

- Cross Country

- Flag Football - Girls

- Football - Varsity

- Football - Junior Varsity

- Golf - Girls Varsity

- Golf - Boys Varsity

- Golf - Boys Junior Varsity

- Lacrosse - Boys Varsity

- Lacrosse - Boys Junior Varsity

- Lacrosse - Girls Varsity

- Lacrosse - Girls Junior Varsity

- Soccer - Boys’ Varsity

- Soccer - Boys’ Junior Varsity

- Soccer - Girls Varsity

- Soccer - Girls Junior Varsity

- Swimming

- Tennis - Varsity Boys

- Tennis - Boys Junior Varsity

- Tennis - Girls Varsity

- Tennis - Girls Junior Varsity

- Track & Field

- Volleyball - Varsity

- Volleyball - Junior Varsity

- Volleyball - Freshman

- Water Polo - Boys Varsity

- Water Polo - Boys Junior Varsity

- Water Polo - Girls Varsity

- Water Polo - Girls Junior Varsity

-

Middle School Teams

- Baseball - Middle School

- Basketball - Boys Middle School

- Basketball - Girls Middle School

- Cross Country - Middle School

- Flag Football - Middle School

- Lacrosse - Boys Middle School

- Lacrosse - Girls Middle School

- Soccer - Boys Middle School

- Soccer - Girls Middle School

- Swimming - Middle School

- Tennis - Middle School

- Track - Middle School

- Volleyball - Middle School

- Athletics Philosophy & Values

- Athletics Resources

- Camps & Clinics

- Alumni Athletes

- New to Menlo Athletics?

- Student Life

- Support Menlo

- Admissions

- Calendar

- Resources

MENLO SCHOOL • SINCE 1915

Menlo News March 15, 2023

Ninth Grade Students Bring Physics to Life

Learning how the world works at the Exploratorium

As part of Menlo’s ninth grade physics curriculum, the entire freshman class visited the Exploratorium in San Francisco. In addition to being a fun and engaging way to bring classroom work to life in a practical setting, students were encouraged to interact with the Exploratorium’s exhibits and discover how physics is not an abstract concept, but a set of explanations of how the world works.

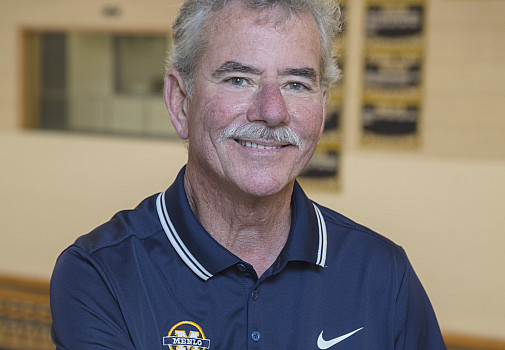

“Teaching physics or science to young learners means that we are fundamentally asking them to suspend disbelief,” said physics teacher James Formato. “We’re asking them to trust that we are curating a set of topics or a curriculum that has meaning in their lives. Addressing that relevance gap is the main work of good teaching because if you can get kids to have buy-in, they will take charge of their learning in ways that can be really satisfying.

“The Exploratorium is a really good opportunity for physics teachers to address that relevance gap by taking students to this place that is basically a shrine to physics curriculum,” he continued. “There are all these exhibits that are straight out of our textbooks. It’s like if you took some of the coolest diagrams from your physics book and turned them into a physically interactive thing. Physics teachers get very excited about that.”

Menlo offers physics in ninth grade as part of a “physics first” curriculum that teaches analytical and conceptual thinking early, building a foundation from which they can explore more complex sciences, such as biology and chemistry. At the Exploratorium, students were asked to choose an exhibit to investigate more deeply, allowing them an opportunity to observe and experiment with phenomena that they have been studying in class. Most importantly, the trip demonstrates to students that their work in a physics classroom has real-world applications.

“My project involved a bicycle wheel that you hold in front of you,” shared Andrew ’26. “You sit in a frictionless chair, spin the wheel, and it creates a gyroscope. The wheel tilts back and forth and rotates, creating a force. Another experiment involved a wheel hanging from a chain. You spin it and watch how it stays upright. I had to research the physics behind it, which involves something called angular momentum, which is the tendency of an object to stay where it is in space and keep its angles. We do a lot of labs in the classroom, but I thought it was a lot of fun that we got to go and see physics out in the world.”

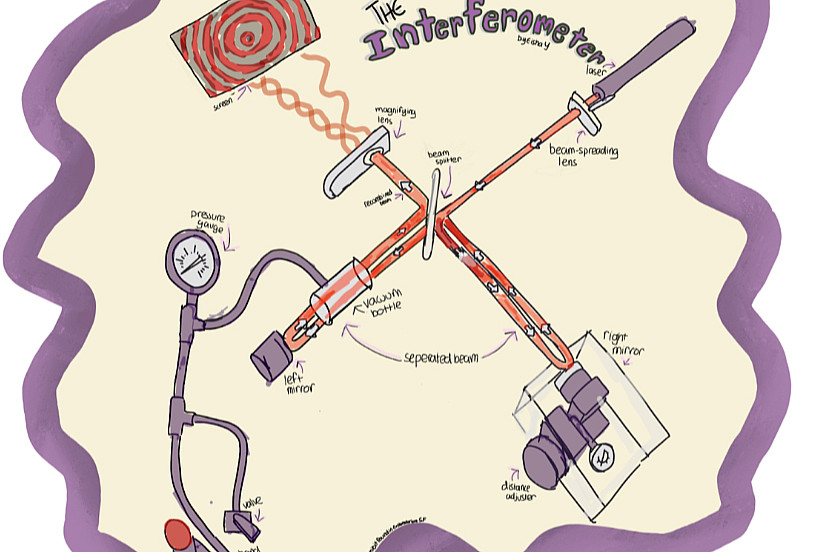

According to Eisha ’26, “For me, it’s really important to have visual representations of the theories and concepts that we’re learning in physics. I was assigned the interferometer, which is a complicated tool that uses light lasers to measure super tiny stuff and even identify gravitational waves. Using art and drawing to encapsulate these ideas are more tangible when you’re able to interact with an exhibit.

“When I came to Menlo, I was not a STEM student,” she added. “I was more into arts and literature. But when I came here, STEM is really where I’ve found my place because my goal for the future is to be able to make a difference in the world. Being exposed to the real-life utilizations of STEM and physics have made me realize that I could use these tools to make something that really changes people’s lives.”

MENLO SCHOOL Since 1915

MENLO SCHOOL Since 1915