- Arts

- Academics

-

Athletics

- Athletics Overview

-

Upper School Teams

- Baseball - Varsity

- Baseball - Junior Varsity

- Basketball - Boys Varsity

- Basketball - Boys Junior Varsity

- Basketball - Boys Freshman

- Basketball - Girls Varsity

- Basketball - Girls Junior Varsity

- Cross Country

- Flag Football - Girls

- Football - Varsity

- Football - Junior Varsity

- Golf - Girls Varsity

- Golf - Boys Varsity

- Golf - Boys Junior Varsity

- Lacrosse - Boys Varsity

- Lacrosse - Boys Junior Varsity

- Lacrosse - Girls Varsity

- Lacrosse - Girls Junior Varsity

- Soccer - Boys’ Varsity

- Soccer - Boys’ Junior Varsity

- Soccer - Girls Varsity

- Soccer - Girls Junior Varsity

- Swimming

- Tennis - Varsity Boys

- Tennis - Boys Junior Varsity

- Tennis - Girls Varsity

- Tennis - Girls Junior Varsity

- Track & Field

- Volleyball - Varsity

- Volleyball - Junior Varsity

- Volleyball - Freshman

- Water Polo - Boys Varsity

- Water Polo - Boys Junior Varsity

- Water Polo - Girls Varsity

- Water Polo - Girls Junior Varsity

-

Middle School Teams

- Baseball - Middle School

- Basketball - Boys Middle School

- Basketball - Girls Middle School

- Cross Country - Middle School

- Flag Football - Middle School

- Lacrosse - Boys Middle School

- Lacrosse - Girls Middle School

- Soccer - Boys Middle School

- Soccer - Girls Middle School

- Swimming - Middle School

- Tennis - Middle School

- Track - Middle School

- Volleyball - Middle School

- Athletics Philosophy & Values

- Athletics Resources

- Camps & Clinics

- Alumni Athletes

- New to Menlo Athletics?

- Student Life

- Support Menlo

- Admissions

- Calendar

- Resources

MENLO SCHOOL • SINCE 1915

Menlo News March 05, 2024

From Mozart to Modernism: Musical Master Classes

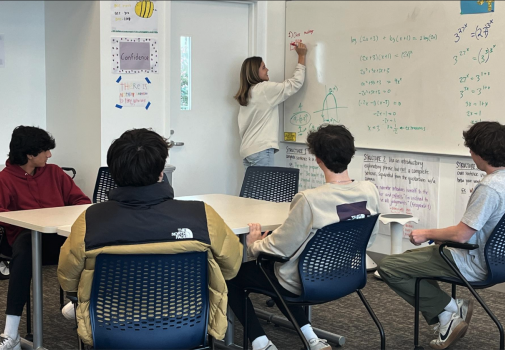

Music@Menlo’s Winter Residency brings top conservatory students to campus to work with Menlo students, connecting classical music to a wide variety of subject areas and allowing students to explore musical movements through a multidisciplinary lens.

Music is a vital component of any Creative Arts curriculum, boosting creativity, curiosity, and self-expression. At Menlo, Middle Schoolers can choose from courses like Jam!: Steel Pan and Percussion, Music Exploration, and Sing! Your Heart Out. In the Upper School, the buffet of options broadens, from Exploring and Expanding Your Musical Taste and Music Theory to Musical Theater and Making Music. Not to mention the more mainstream performance-oriented offerings: choir, acapella, orchestra, and jazz.

But not all opportunities to learn from music take place through the Creative Arts. Margaret Ramsey’s Lyric and Lifeline explores hip-hop’s origin story from a historical, political, spiritual, and economic perspective; Oscar King’s East Asian Pop Culture examines the profound impact and influence of K-Pop on global culture; and, for two weeks every February, Music@Menlo’s Winter Residency program has been leading curated experiences for Menlo students to dive into other disciplines through the lens of music.

This year’s Winter Residency featured 18 distinct presentations for hundreds of students from Middle through Upper School. The performances guided each class on a thoughtfully designed journey throughout classical music history, each subject matter offering a different lens and perspective. The reprise? The power of music to expand how view the world, its history, and our place in it.

About Music@Menlo’s Winter Residency

Music@Menlo is an internationally acclaimed chamber music festival and institute held every summer at Menlo School. Since 2005, Music@Menlo’s Winter Residency has brought some of the best conservatory students from around the country to campus to work with Menlo students, connecting classical music to a wide variety of subject areas. Each session is tailor-made in collaboration with Menlo faculty to align with and enhance what the students are learning in class.

This year, violinist James Thompson curated the program, conducting a symphonic journey of interactive lessons that transported students through the musical ages, finding throughlines between historical context and composition. He was joined by pianist Kevin Ahfat, cellist Andrew Byun, violist Laura Liu, and violinist Nathan Meltzer, all graduates of Music@Menlo Chamber Music Institute’s International Program, a prestigious summer program inviting eleven outstanding conservatory-level musicians to learn from world-class chamber music artists and educators.

“We hope that by making these connections between music and history, philosophy, architecture, design, visual arts, languages, and more, Menlo School students may develop a deeper appreciation for a type of music they may not be familiar with,” says Daphne Wong, Music@Menlo’s Director of Artistic Administration. “The music performed and discussed also provides valuable insight into cultural, artistic, and historical periods that students may not have previously discovered or explored.”

What is Art?

For the past 10 years, Jack Bowen’s Philosophy class has concluded their focus on the philosophy of art with the Music@Menlo Winter Residency presentation. In the week prior , they had been exploring questions like, “What is art?” and “What is good art?” (a la Tolstoy) as well as whether the government should fund art through the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). Mr. Thompson kicked off the session by asking students to write down what they considered to be the dictionary definition of music, and to contemplate what makes music “good” or “bad.”

“For me, it was based on a lot of what we talked about in class, which is about how art needs to be able to evoke some sort of emotion. And so music is like a collection of sounds able to evoke something,” said a student. “I also think that music is like a form of communication between whoever writes the music, the person who plays the music, and the person who’s listening to the music,” added a classmate. “And it can be like a form of self-expression—how you express yourself through the music and how people interpret that.”

At this, Mr. Thompson shared his plans to expand the students’ meanings during the session. “My hope is that we’re going to share some music that you’ve never heard before, maybe on the fringes of what you actually define as music, to kind of stretch this definition throughout the class,” he said.

Between musical interludes corresponding to the times of various philosophers and ideologies they’d been studying, the class engaged in lively and thoughtful debates about whether good music should make you feel good, whether composer John Cage’s 4’33” is considered music (the class was equally divided), and whether context is necessary for music to be beautiful. “Even after 10 years of doing this, I still come away from it with a new perspective and new ways of viewing philosophical concepts such as beauty and art itself,” said Mr. Bowen.

The parallels between music and philosophy are profound. For example, what could depict the Age of Enlightenment—the “I think, therefore I am” mentality—better than Mozart? In introducing his Divertimento for Violin, Viola, and Cello in E-flat major, Mr. Thompson took us back to a time when the world was looking towards science, logic, structure, and reason to form a better civilization, moving out of centuries of feudalism towards something that was a little bit better for humanity. “It was this attitude, this philosophy that impacted all of the music that was being written during this time,” he said as the musicians lifted their bows, made eye contact, nodded, and began to play.

The Architecture of Music

Marc Allard’s Design & Architecture course studies architectural movements over the past 250 years, from Neoclassical to Art Deco, Prairie-style to Deconstructivism. Given that context, Mr. Thompson carefully curated this class’ repertoire to correlate with those periods. “Architectural movements don’t form in a vacuum,” said Mr. Allard. “They are reflective of what is happening in society and culture at the time.”

The presentation walked students through the founding of this country in the 18th century where music and design featured structure, order, and optimism with an uplifting, hopeful feel. As we move towards the 19th century—the romantic era—the music becomes more turbulent and emotional. Architecture from this time period is equally as evocative: imitating ancient castles, churches, and fortresses.

At the turn of the 19th century, inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright and the Prairie School Movement, an emphasis on nature, craftsmanship, and simplicity emanated a sense of nostalgia for a bygone era. After Mr. Thompson pointed out the likenesses between Wright’s sweeping horizontal lines, vast expanses of middle American landscape, and long, open harmonies in the classical music of that time, the musicians performed a piece by Charles Ives, known as the quintessential American sonata, with strains of Civil War America and a simpler time.

In the early 20th century, sentiments of fear and unpredictability surrounding the start of World War I catalyze the expressionist, early-modernist movement in the arts. Mr. Thompson compared the work of composer Schoenberg to visual artist Kandinsky, both conveying abstract elements through art and music. Just as musicians were experimenting with new types of sounds, the architecture of the time reflects the use of new types of materials. As composers began shortening their works, architects used fewer materials in their designs.

In stark contrast stands the Art Deco movement, hearkening to the Roaring Twenties, adorned with economic prosperity and an air of positivity shining from every gilded surface. Music, art, and architecture of the time incorporate global influences as traveling across oceans became more common and the exchange of ideas permeated cultures and continents. Jazz, already ruling the U.S. musical roost, became an international sensation, influencing composers across the world.

Music@Menlo’s expedition through architectural movements ended with Deconstructivism, which Mr. Thompson described as a sort of “3D Picasso,” taking something normal looking and distorting it, warping it, taking it apart and elongating certain things and chopping it up a bit. He compared this concept musically to the second half of the 20th century, in which composers pulled music apart to the point where it was almost unrecognizable, tweaking it in wild ways to come up with something previously unheard of. The musicians exemplified this concept with Schnittke: Piano Quintet mvt. II, where the composer divided the 12 notes of the scale in half, with string instruments playing between what are normally considered the pitches of the scale, creating a chaotic, kaleidoscope effect. The piece was frenetic, unconventional, and much like the way deconstructivism is described, “developed to oppose the ordered rationality.”

MENLO SCHOOL Since 1915

MENLO SCHOOL Since 1915